What’s at stake when you make a picture in a public space

July 15, 2009That the crown of the Statue of Liberty just reopened for the first time in nearly eight years is heartening, perhaps another small sign of the thaw in accessibility of public (and even historic and symbolic) places in the twenty-first century. Of course it’s not so much the restrictions on physical entrée that have signaled our compliance with post-9/11 command and control structures; what’s largely ignored are the mental battles—of images and their interpretations, of access to public space and full engagement with the environment we’ve built.

What obviously first comes to mind is the inverse propaganda, the successful curb on pictures of our wars and of soldiers’ coffins (a rule lifted by the Obama administration). But even closer to most of our experiences is the pervasive and baseless clampdown on making photographs in public and publicly accessible spaces. The reports of photographers being harassed, detained, and threatened with arrest are now legion (my favorite anecdote being Keith Garsee’s who was confronted by an enthusiastically ignorant security guard who cited something called the “9-11 law”).

Some cases received a lot of publicity due to high irony factors, such as when Duane Kerzic was arrested in late December 2008 by Amtrak Police for photographing a train at Penn Station. Why was he doing this? Because he was going to enter his photos of Amtrak trains a contest called Picture Our Trains—sponsored by Amtrak! The level of absurdity here is funny until a malevolent visage, still hard to shake, creeps into my mind’s eye.

There are a few things going on here, some of them explicable—if no less wrong—on account of human nature. But there is arguably another, more important level of struggle at hand, bound up in control over images and access to our built environment; if these rights are lost it will be through our voluntary and conscious relinquishment.

The first level is easy to figure out: after 9/11 we outsourced our rights. It’s not just the actual consequences of the letter of the Patriot Act, or the totally out-of-control Terrorist Watch List (now 1,000,000 names strong! Even if tens of thousands of those names are admittedly wrong). Worse than actual restrictions on freedom is the persistent perception of these constraints. To be clear: the Patriot Act did not overturn or even alter the First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America. Taking photographs on and of public property—and even most private property from the vantage of public property—is 100% legal. But somehow the post-9/11 environment has led people to assume this is not the case; ignorance begets ignorance. Almost everyone is to blame here: latent power complexes possibly harbored by cops, TSA employees, and private security guards are allowed to develop into full-blown petty tyranny in this climate. And otherwise sensible citizens routinely surrender in the face of such displays of power.

Surveillance camera on the Mercantile Exchange Building, Battery Park City, New York. Shot from public space, though a guard tried to stop me from taking this photo.

From what I’ve experienced firsthand and observe anecdotally, a private security guard is a lot more likely to try to restrict lawful picture-taking than a cop. Cops get the law wrong too, but for the most part they know that if you are on public property you are free to make images (if not, and you’re in New York, remind them of the Operations Order issued in April 09 that photography is not a crime). Private, for-profit forces, here and abroad, took on security details with incredibly broad but entirely vague mandates, answering not to civil society, but to their bosses.

I acknowledge the difficulty in making umbrella statements about this. But unless someone is going to try to enact and enforce legislation to register every camera and cellphone in the country, everyone has to admit the genie left the bottle long ago. A Canon 5D with a 70-200mm lens makes no more real of a photo than the one taken with an iPhone. The photographers who get harassed are merely conspicuous, which is what anybody has a right to be when engaging in a legal and socially acceptable activity.

But the subtler level here, and why I think it’s important to not just raise awareness but actively resist these restrictions, is that we are all caught up in a grand struggle of ideas and images, and for the most part don’t even know it. This is a use it or lose it moment.

As Marshall Berman relates in his epilogue to “A Times Square for the New Millennium,” even innocent observation is too often mistaken for surveillance. In response, concerned photographers have created photog-mobs—organized picture-taking manifestations that overwhelm security and challenge their misunderstanding of the law.

The number of people raising their voices about this issue is growing. Cory Doctorow’s coverage at Boing Boing is very good, and individuals like Kerzic and Carlos Miller (Photography is Not a Crime) keep pushing the issue on their sites and directly to authorities. Matthew Williams satirically made fake licenses (1, 2) to present when prompted by out-of-touch security forces.

This isn’t just an issue for “professional” photographers; now digital cameras and cell-phone cameras are so pervasive, we are all arguably photographers. For many nonprofessionals whose interests lie in design and architecture, photography is an essential research tool that helps record and understand our built environment. Beyond this professionally specific group, it is as important as ever for every citizen to feel engaged with their towns and cities. When this is lost, we tend to foster and tolerate places that aren’t worth being in. This is disenfranchisement of a fundamental kind: for the majority of the populace, the built environment is still what happens to them and around them—not what it feels it can create.

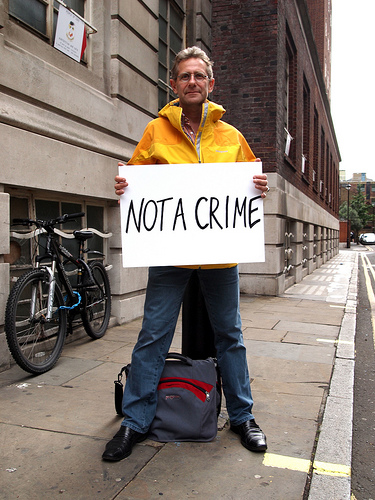

It is high time to rethink this. In a paranoid America (and UK, where our best-mates-forever have also been very assiduous in keeping their territory clear of potential photo-terrorists–there are many recent scary stories on the British Journal of Photography, an excellent resource overall), authoritarian control has crept further into our lives, largely by our consent. We have been too complicit in our newfound constraints. Go learn about an environment you like: find some public space and take pictures. And challenge anyone who tries to stop you to cite the law that prohibits photography. Know your rights and support new projects such as the newly launched Not A Crime: “Over the next year, we hope to gather thousands of self-portraits of photographers—professional and amateur—from around the world, each holding up a white card with the words: ‘Not a crime’ or ‘I am not a terrorist.’”

The operating philosophy here is that the biggest jail is in our own heads, and that a society gets the freedom it earns. Let’s turn it around.

A friend working on a movie in Berlin just mentioned in an email her shock at German indifference to photography in public space. They’ve shot — without permit, using a biggish DV camera — in train stations, plazas, streets, in front of various official buildings, and so on. Any sense of why Germany is so chill on this score?

the photographer also poses legal challenges of the copyright variety. for instance: is a photograph of the guggenheim museum clear? for what purpose? according to whom?

Well, there are a number of artists who try to restrict image-making of their works. Anish Kapoor tried with Cloud Gate on a copyright basis–and failed, because Millennium Park is public (but not before park guards harassed people for photographing it: http://www.metafilter.com/39546/Copyrighting-public-space).

Walter De Maria and Dia would like you to not make photos whilst visiting Lightning Field–but then you are on their grounds.

But if it’s in your eyespace and you are on public ground, it seems up for grabs.

This is a great piece. Thanks for mentioning me.