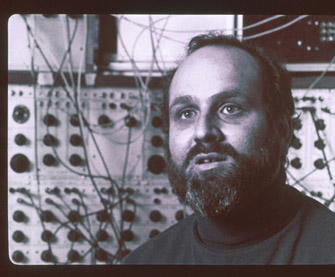

These great stills from an educational filmstrip show a mod Morton Subotnick in his Bleecker Street studio, most likely in the early 1970s. The analog synth apparatus here is the Buchla Modular Electronic Music System 100 series, which Don Buchla constructed from a spec by Subotnick and Ramon Sender. Subotnick resurfaced in my consciousness recently after attending the 45th Anniversary of Terry Riley’s In C (mentioned here earlier). Subotnick joined the 60+ musicians onstage on clarinet, which he played professionally prior to his career as a pioneering electronic music composer and musician. Subotnick is cofounder of the San Francisco Tape Music Center, a crucible of early electronic music whose influence on contemporary music is impossible to quantify. Its members included Subotnick, Sender, Pauline Oliveros, Tony Martin, and William Maginnis. (In an amusing twist, the former site of the SFTMC at 321 Divisadero is now the yoga studio in which my wife practiced).

The Buchla is what you hear on Subotnick’s early Nonesuch releases Silver Apples of the Moon (1967) and The Wild Bull (1968). Obviously technology and compositional techniques now far supersede these recordings, but what makes these listening experiences so incredible is still the sense of true novelty—these machines making these sounds for the first time. Today it may seem shambling, squawky, and warty, but this uncanny music charted entirely new terrain.

The history of the Tape Music Center is covered in this amazing book from UC Press, The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, with essays by and interviews with the Center’s founders as well as collaborators and contemporaries Terry Riley, Stewart Brand, Ann Halprin, and Stuart Dempster. My old friend Tom Welsh contributed his own independent research to the book and assembled the incredibly detailed chronology.

This passage by Subotnick in the book gives a glimpse of how blazingly fast electronic music developed in the late 1960s, and how prescient his vision was:

. . . I was in New York for a performance and made an appointment with the Rockefeller Foundation. . . . Since they had helped fund the Columbia-Princeton studio, I presented our dream. We would like the funding to work with electronics and sound in San Francisco. Soon people would be able to create with sound in their living rooms. We had developed a notion, not of an electronic organ, but of a sound easel that was closer to an analog computer, with which people could create with sound the same way they had always been able to create with paint and paper. With $500 for parts and a little more for some other equipment, we could create a facility centered around this idea.

The response of the Rockefeller Foundation was that, though it appreciated what we were trying to do, its view was that there would never be enough interest in this kind of thing to warrant a second studio in the United States. . . .

Subotnick moved to New York in 1966 and became artist-in-residence at the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU (who granted him enough money for the Buchla). Here his musical experimentation flourished.

By the end of 1967, two years after I left San Francisco and the Tape Music center was transferred to Mills College, I was living in a world quite different from the one I had inhabited a few years earlier, in which it had been supposed that there would “be so little interest that it would be cheaper to fly people to New York from all over the world than to build a second studio.”