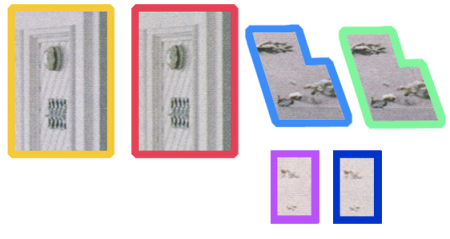

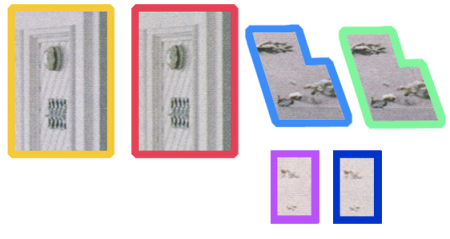

- Photo District News further identifies “evidence of manipulation” in Edgar Martins’ photographs.

The Edgar Martins episode may be fading quickly, but the underlying issues won’t; they predate the digital era and will outlive the current edition of Adobe Photoshop.

What has interested me in this kerfuffle is how it has revived what I thought were fairly settled debates around image manipulation—er, alteration. Postproduction??—but this hunt for some morally neutral, aesthetically precise vocabulary to merely describe a commonplace photographic process reveals a persistent and deeply ingrained prejudice against it. (The editors’ note on the Times site itself betrays this rhetorical delicacy: “Editors later confronted the photographer and determined that most of the images did not wholly reflect the reality they purported to show.”)

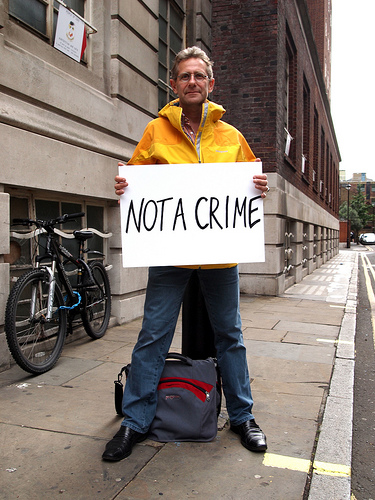

Of course it was Martins’ assertion that he doesn’t employ such techniques, paired with a flagrant violation of the New York Times’ ostensible photojournalistic objectivity, which raised clucking disapprobation (as well as the slackness of the work, which is also pointed out in tones of disapproval). But I am still surprised that the “fixed image”—a term that harkens to photographic darkroom practice, when the image is chemically stopped before it flees—is still regarded as a sacrosanct artifact, even today, even among an increasingly visually literate populace, much less people who for better or worse spend time thinking about aesthetics.

But as a non-practitioner, I think my opinion counts only so far in this discussion, so I turned to several accomplished photographers who have dedicated commercial, editorial, and art-practice work to architecture. But like every debate, this one needs to be framed, so I contrived a question as essentialized as I could (though I also admit the question itself harbors a bias): should photojournalistic standards of “truth” be applied to architectural photography? So please read the responses below from Alex Fradkin, Tim Griffith, Mark Luthringer, and David Maisel, each of whom probe at these very issues in their own intelligent and diverse photographic work. I hope to post opinions from more photographers shortly.

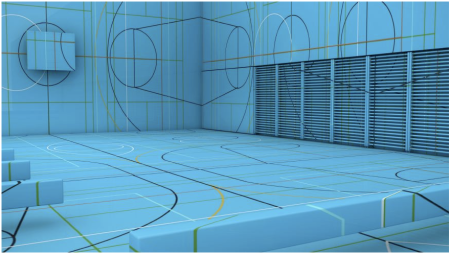

My first reaction when seeing the images that were altered by Edgar Martins was not one of having been scandalized, deceived, or my questioning his ethics. Instead, when comparing the original and the final images that ended up in the Times Magazine, I wondered why he chose to make the images less compelling, by making them perfectly symmetrical. I have always like Martins’ work, still do. His photographs clearly belong in the fine art genre and not photojournalism. His work in my opinion has never been about depicting reality. I see his work as using what is “real,” as a departure point for the open-ended narrative of fiction and surrealism. Juxtaposing Martins’ images, with his established aesthetic is inherently problematic. Additionally, Martins’ should have understood that his images would be accompanying a journalism piece in a magazine that has a very clear stated policy regarding manipulated images. The Times Magazine’s stated guidelines are not difficult to interpret. To make matters worse, the Times described the project as not being digitally manipulated.

Architectural photography has varying rules regarding digital manipulation. Most magazines have stated policies outlining these policies. When commissioned by a client, the architectural structure is depicted in its most complimentary light and composition, where visual clutter and tones are adjusted. The boundary from photo to digital illustration is often crossed resulting in an image that looks more like a hybrid photo/computer generated image. In fine-art architectural photography, anything goes. Just be clear and consistent when asked if the image has undergone digital manipulation.

In the case of Martins, who probably does not see himself as being bound by “journalistic standards of truth,” and possibly even a little dismissive of those standards, ended up being commissioned by a magazine that is often a lightning rod for those who question the veracity of popular news media. Simply, a very poor choice on his part added to his being published in one of the most sensitive and visible media outlets. If his images had shown up in an architectural magazine, this controversy probably would have never materialized. If these images had shown up in fine art architectural book or on a gallery wall, the mirrored and partially duplicated parts of the images would have been seen as part of the artist’s intention. The discussion would then have focused on fictional narratives and the inherent meaning of what was intended by the photographer.

His comment about not employing post-production techniques was made over a year ago and to my knowledge has not been restated. Change and experimentation are an artist’s prerogative and part of the recent controversy surrounds that statement he made in 2008. Clearly he has changed this policy, but has made an unfortunate choice in the wrong venue to show his new methodology. Comparatively egregious, the alterations degraded the final works and were somewhat amateurish and easily spotted. At least if you are going to fall on your sword, make it for a truly worthy cause and do it well.

In the book Architecture Transformed: A History of the Photography of Buildings from 1839 to the Present Cervin Robinson and Joel Herschman described a period in which the photography of built form diverged into two distinct camps. The pragmatic, documentary style exemplified by the likes of Walker Evans on one hand and the more aspirational, suggestive imagery of Hedrich Blessing, Ezra Stoller, and Julius Shulman on the other. Modernist architecture was just gaining a foothold in the United States and needed strong visual representation to help “sell” it to the wider public. The compelling images of sleek factories, elegant civic projects and bright, open residences were instrumental in driving the popularity and general acceptance of this architecture.

Cervin Robinson and Joel Herschman described a period in which the photography of built form diverged into two distinct camps. The pragmatic, documentary style exemplified by the likes of Walker Evans on one hand and the more aspirational, suggestive imagery of Hedrich Blessing, Ezra Stoller, and Julius Shulman on the other. Modernist architecture was just gaining a foothold in the United States and needed strong visual representation to help “sell” it to the wider public. The compelling images of sleek factories, elegant civic projects and bright, open residences were instrumental in driving the popularity and general acceptance of this architecture.

These were crafted, commercial images, made with a particular outcome in mind. Their role was to do more than merely inform the viewer of the building’s existence. They gave voice to the promise of a better future. A sleek, modern, prosperous new life.

But can these images be considered “truthful”? Depends who’s asking.

Even in this digital age, the initial act of choosing where to place the camera can be as politically charged as any amount of retouching or outright fabrication of specific elements with the frame. A potentially controversial design can be softened by selecting a flattering angle, choosing a flattering time of day, including more or less of the surrounding context. This is considered normal practice for an architectural photographer.

The majority of commercial architectural photography is commissioned by those with a vested interest in portraying the project in a good light. So photographers tend to seek solutions that satisfy that outcome. To do otherwise would likely shorten your career considerably.

With the easy availability of tools to digitally manipulate photographs, there is a certain commercial expectation from clients that some degree of “cleaning” will be undertaken during production of the final image. The words “we can fix that up later, right?” are becoming all too familiar. This “fixing” can either be handled by the photographer, or potentially by the client in-house. My preference is to control the retouching to ensure it is done within the bounds of providing a realistic representation. Realistic perhaps, as opposed to truthful.

One thing driving the widespread manipulation of architectural images is the commercial desire for finished views of the project well in advance of the actual completion date. Buildings are completed digitally so that marketing and advertising material can be generated. This manipulation is equally as applicable and important to museums and civic centers as it is for commercial developments and residential leasing companies.

Is this the actual truth as of this moment in time? Or can it be seen as advancing the truth, bring it forward a little? I mean the building will look like that, just not quite yet. And are these digital manipulations any more or less truthful than the computer renderings that had been used to represent the design through planning and construction?

The manipulation of commercial architectural images has become so commonplace that almost no other views of architecture are visible in our culture. Robert Elwell, in his excellent book Building With Light: An International History of Architectural Photography , suggests there are now only are two ways in which architecture is being presented to the world. The first is in the sleek, manipulated, politicized images made for commercial or marketing purposes. The second is within the fine art world where the architecture itself seems to be of much less importance than the artist making use of it as their subject. Elwell laments the time when photography played a more critical role in how architecture was represented, when there was some social commentary within the images on the appropriateness, or not, of new developments.

, suggests there are now only are two ways in which architecture is being presented to the world. The first is in the sleek, manipulated, politicized images made for commercial or marketing purposes. The second is within the fine art world where the architecture itself seems to be of much less importance than the artist making use of it as their subject. Elwell laments the time when photography played a more critical role in how architecture was represented, when there was some social commentary within the images on the appropriateness, or not, of new developments.

Realistically though, images that are less than flattering to architecture are simply not viable these days. They are potentially damaging commercially. They are less likely to get published by the design press that relies heavily on funding from advertisers with vested interests. No-one wants to see aluminium panels rippling badly in raking light. No-one wants to see the awful concrete rubbish bins along a facade because the developer/client was too cheap to purchase the ones suggested by the architect. No-one wants to see “For Lease” signs in a supposedly bustling retail center.

They want to see the constructed reality, not the truth. And as commercial architectural photographers, that’s what we get paid to provide. A friend of mine coined the phrase “really truthy lies.”

So to answer your initial question. . . . No. I don’t believe that a photojournalistic standard of truth can be applied to commercial architectural photography. To do so would make it unsustainable economically for the majority of those employed as architectural photographers.

So you can’t get architectural photographers to shoot the truth. As recently proven by Edgar Martins, you can’t expect a fine artist to tell the truth. I suppose you could get a photojournalist to shoot the truth but then perhaps, it becomes more about social context than about the architecture itself.

In any case, all three of these [kinds of] photographers can produce a version of the reality. Whichever one of the three is considered more truthful largely depends upon the inherent values of the particular audience involved. Clearly, the truth as accepted by the fine art world becomes increasingly fragile and dubious when held up to the wider scrutiny of a more cynical and hardened public.

No, generally speaking, I don’t think photojournalistic standards of truth should be applied to client work. They are pictures for selling, and as such should be enhanced as much as possible to make them into better pictures. Here it becomes a matter of taste and judgment. But a distinction must be made between making a picture prettier, sexier, or whatever, and actually fabricating structures, objects, etc. This is something I wouldn’t go along with, unless the client was specifically directing me. . . .

What bothers me about the whole Martins thing goes back to taste and judgment—Martins’ but more especially the NYT people. Surely [this is] very embarrassing for them (the digital work is very sloppy), but they are the ones who seem to want it both ways.

Maybe we can finally rethink the whole notion of having so-called ‘fine art photographers’ do editorial work. It’s a devil’s bargain and almost always a dismal outcome for each side (editor and photographer) in my opinion. If Martins is a ‘fine art photographer,’ then oughtn’t he be afforded wide latitude in his strategies and the kinds of images he makes? If so, then why is NYT hiring him for ‘journalistic’ work? To me, they’re idiots and have been for years. . . .

As for Martins, what does he hope to gain by all this cloning and stamping, mirroring and flipping? THIS is the ‘fine art’ in ‘fine art photography’?? Well, what is he supposed to do? His experience, and his imagery, show that he is coming up against the inevitable, the immovable, the inescapable, and that he knows there’s just not enough for him to do.

There is no such thing as photographic truth, in architectural photography or any other kind of photography for that matter.